I typically end up taking the role of “build guy” and I have no idea why! It is probably a control thing; I like to be able to fix problems and make improvements. I have been an Ant-man for many years, and was proficient in the “Art of Make” before that. I never gave Maven a chance, as it always seemed like it was too complicated for adoption by corporate projects. Ant can be very simple and quick; some might even throw the word dirty in there!

I typically end up taking the role of “build guy” and I have no idea why! It is probably a control thing; I like to be able to fix problems and make improvements. I have been an Ant-man for many years, and was proficient in the “Art of Make” before that. I never gave Maven a chance, as it always seemed like it was too complicated for adoption by corporate projects. Ant can be very simple and quick; some might even throw the word dirty in there!  Unfortunately, I have seen (hopefully not created!) some of the most horrific Ant build systems imaginable. Many times, it is a developer’s “first time effort” that becomes the project’s permanent build system. Because I had the opportunity to work on many different Ant-based projects, I gained experience by using and evaluating many different approaches. I believe that real problem with Ant, is not necessarily Ant itself, but the lack of standards and structure it provides. Ant allows each developer (or project) to invent its own Ant Philosophy. Once you are familiar with the Ant “programming style”, you can script just about anything, any way you want, manipulating files located in any direct structure, located anywhere on the network. Ant is a very powerful and flexible tool. Unfortunately, the more inventive the Ant Philosophy is, the more brittle and complicated the scripts can become. Ant XML also seems to be an excellent “cut and paste” candidate. New team members, with little time or understanding of Ant or the specific philosophy implemented, find duplicating targets the safest method to implement change. Another shortcoming of

Unfortunately, I have seen (hopefully not created!) some of the most horrific Ant build systems imaginable. Many times, it is a developer’s “first time effort” that becomes the project’s permanent build system. Because I had the opportunity to work on many different Ant-based projects, I gained experience by using and evaluating many different approaches. I believe that real problem with Ant, is not necessarily Ant itself, but the lack of standards and structure it provides. Ant allows each developer (or project) to invent its own Ant Philosophy. Once you are familiar with the Ant “programming style”, you can script just about anything, any way you want, manipulating files located in any direct structure, located anywhere on the network. Ant is a very powerful and flexible tool. Unfortunately, the more inventive the Ant Philosophy is, the more brittle and complicated the scripts can become. Ant XML also seems to be an excellent “cut and paste” candidate. New team members, with little time or understanding of Ant or the specific philosophy implemented, find duplicating targets the safest method to implement change. Another shortcoming of  Ant is dependency management. This problem is easily solved and have blogged about it numerous times in the past. I believe that the use of a dependency management tool, such as Ivy, is an evolutionary step taken by “build guys”. Sadly, many developers don’t seem to be interested in dependency management. They don’t like the dependency on the dependency management tool and would rather just manage them within the project. For me, the value of the central repository and structurally documented, versioned dependencies cannot be undervalued.

Ant is dependency management. This problem is easily solved and have blogged about it numerous times in the past. I believe that the use of a dependency management tool, such as Ivy, is an evolutionary step taken by “build guys”. Sadly, many developers don’t seem to be interested in dependency management. They don’t like the dependency on the dependency management tool and would rather just manage them within the project. For me, the value of the central repository and structurally documented, versioned dependencies cannot be undervalued.I have probably described many of the same experiences you have encountered with Ant-based projects; they can be even more exaggerated when you start managing multiple projects. One possible evolution path is to define a “standard” directory structure and develop a collection of “shared” Ant scripts that work with the standard directory structure. This allows each individual project’s build XML to be little more than a set of properties. This is exactly where we ended up, utilizing an Ivy-like externalized repository for build scriptlets and Ant’s URL import capability. Hold on, a standard directory structure with reusable build components? Almost sounds like some other tool…

| The Experiment… |

| Being an Eclipse guy, I was curious how to combine an Eclipse Web Tools Platform (WTP) project with a Maven project. My ultimate goal was to setup a Jenkins Continuous Integration Server, that monitored a Maven-based project on GitHub, and develop the code within Eclipse and utilizing a Dynamic Web Project facet. Historically, my projects were managed by Hudson using Free-style jobs; they were always Ant-based and extracted from a Subversion repository. I had worked on quite a few web applications using this pattern, so it seemed like a pretty good starting point! I had started a toy project to manage encrypted data a couple of years ago and never put it under version control, it was a perfect candidate for this experiment. |

Changing a project’s build tool has a rather large impact and needs be considered from multiple perspectives. I have approached the problem by breaking it down into five (5) different spaces. This might not be the optimal or preferred approach, but does show the high-level differences and addresses the major build challenges. Surely, my next project will be done completely differently, but you have to start learning somewhere!

| Perspective | Changes |

| Dependencies | To end up with an application that compiles in Eclipse, this change and the next have to be done in parallel. The easiest approach is to create a POM and focus on the dependencies section. If you are already using Ivy to manage your dependencies, this will not be that big of a change. Using a public Maven repository like MVN Repository to locate dependencies is very simple and saves a ton of time. The easiest way to create a POM is to let Eclipse make it for you; you will need to install the Maven plug-in first. Once you have your project loaded into Eclipse, simply “Enable Dependency Management” in your project’s properties. You can also add dependencies directly from the plug-in; I’m a little old school and prefer to edit the POM manually, but either approach works fine. |

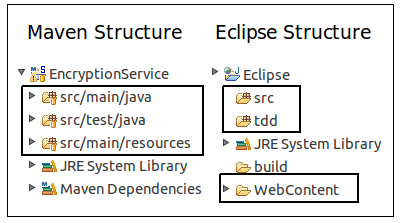

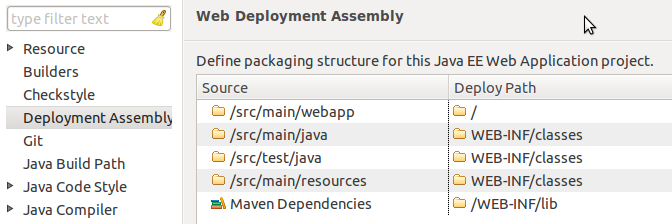

| Local Development |  I never liked the required Maven directory structure; I must have subconsciously adopted the Eclipse project structure as my personal standard. Converting the project’s directory structure was trivial and soon realized it was not that big deal after all; I aways separate my source and test files anyway. The main difference is everything lives under the source root, including the WebContent directory. I’m not sure what the “preferred” process is for loading a Maven project into Eclipse, probably using the Maven Eclipse Plug-in, which will create the appropriate Eclipse property files. Since I was doing a conversion, I don’t think this plug-in would be too helpful. Because I’m fairly Eclipse savvy, I simply wired everything up myself. Having the Eclipse Maven Plug-in will enable your dependencies to be automatically added to the build path. I never liked the required Maven directory structure; I must have subconsciously adopted the Eclipse project structure as my personal standard. Converting the project’s directory structure was trivial and soon realized it was not that big deal after all; I aways separate my source and test files anyway. The main difference is everything lives under the source root, including the WebContent directory. I’m not sure what the “preferred” process is for loading a Maven project into Eclipse, probably using the Maven Eclipse Plug-in, which will create the appropriate Eclipse property files. Since I was doing a conversion, I don’t think this plug-in would be too helpful. Because I’m fairly Eclipse savvy, I simply wired everything up myself. Having the Eclipse Maven Plug-in will enable your dependencies to be automatically added to the build path.  With the addition of the Eclipse “Deployment Assembly” options dialog, it is extremely easy manually configure your project. You need to have a Faceted Dynamic Web Module for the “Deployment Assembly” option to be visible, but that should be a fairly simple property change as well. At this point, you should have a fully functional, locally deployable web application. With the addition of the Eclipse “Deployment Assembly” options dialog, it is extremely easy manually configure your project. You need to have a Faceted Dynamic Web Module for the “Deployment Assembly” option to be visible, but that should be a fairly simple property change as well. At this point, you should have a fully functional, locally deployable web application. |

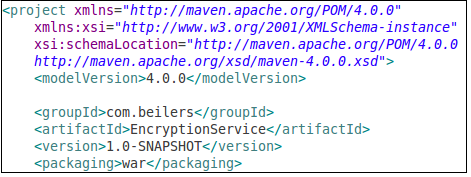

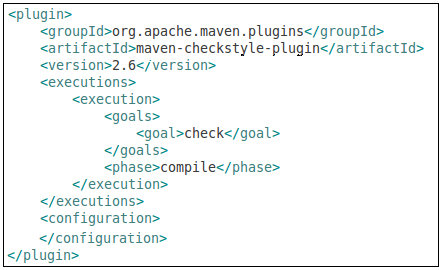

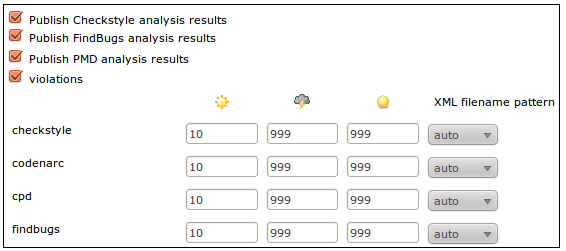

| The Build |  Now we can ignore Eclipse, and focus on building our WAR file using Maven. Even with the minimalist POM shown to the left (plus your dependencies section), it is possible to compile the code and create a basic WAR file. Use mvn compile to ensure that your code compiles. Using the Maven package goal, the source code is compiled, the unit tests are compiled and executed, and the WAR file is built. All of this functionality, without writing one line of XML! Now we can ignore Eclipse, and focus on building our WAR file using Maven. Even with the minimalist POM shown to the left (plus your dependencies section), it is possible to compile the code and create a basic WAR file. Use mvn compile to ensure that your code compiles. Using the Maven package goal, the source code is compiled, the unit tests are compiled and executed, and the WAR file is built. All of this functionality, without writing one line of XML!  One of the more time consuming parts of an Ant-based build is integrating all of the “extras” typically associated with a project, making them available to the continuous integration server. The extras include: unit test execution, code coverage metrics, and quality verification tools such as Checkstyle, PMD, and FindBugs. This tools are all typically easy to setup, but every project implements them slightly different and never put the results into a standard place! The general process for adding new behavior (tools) to a build appears to be the same for most tools. You simply add the plug-in to the POM and configure it to fire the appropriate goals at the appropriate time in the Maven lifecycle. Ant does not have this lifecycle concept, but it seems like a very elegant way to add behavior into the build. From the following example, I added the Checkstyle tool to the POM. The <executions> section controls what and when the plug-in will be executed. In this example, the check goal will be executed during the compile phase of the build process. Simply executing the compile goal, will cause Checkstyle to be invoked as well. This seems like a very clean integration technique, one that does not cause refactoring ripples. One of the more time consuming parts of an Ant-based build is integrating all of the “extras” typically associated with a project, making them available to the continuous integration server. The extras include: unit test execution, code coverage metrics, and quality verification tools such as Checkstyle, PMD, and FindBugs. This tools are all typically easy to setup, but every project implements them slightly different and never put the results into a standard place! The general process for adding new behavior (tools) to a build appears to be the same for most tools. You simply add the plug-in to the POM and configure it to fire the appropriate goals at the appropriate time in the Maven lifecycle. Ant does not have this lifecycle concept, but it seems like a very elegant way to add behavior into the build. From the following example, I added the Checkstyle tool to the POM. The <executions> section controls what and when the plug-in will be executed. In this example, the check goal will be executed during the compile phase of the build process. Simply executing the compile goal, will cause Checkstyle to be invoked as well. This seems like a very clean integration technique, one that does not cause refactoring ripples.

The Cobertura integration is another very good example. I have been a fan of the Clover code coverage for many years. Since losing access to Clover, I needed to look for an open-source alternative, and had never tried EMMA or Cobertura. They both seemed like capable tools, but I had more success integrating Cobertura with Jenkins. I’m highlighting this point, as doing code coverage with Ant and Clover can sometimes be a little tricky and usually messy. The Cobertura plug-in takes compete responsibility for instrumenting the code, executing the unit test, and generating the report; completely non-intrusive. |

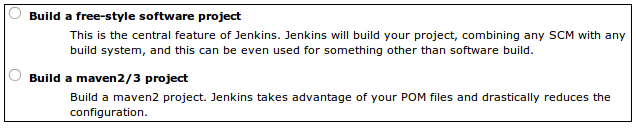

| Continuous Integration |  Most development teams also want their project monitored by a Continuous Integration (CI) process. Modern CI tools such as Hudson/Jenkins provide excellent dashboards for reporting a variety of quality metrics. As I previously stated, it is rather time consuming to develop and test the Ant XML required to generate and publish these metrics; combine that with configuring each CI server job to capture these metrics and you have added a fair amount of overhead. Most development teams also want their project monitored by a Continuous Integration (CI) process. Modern CI tools such as Hudson/Jenkins provide excellent dashboards for reporting a variety of quality metrics. As I previously stated, it is rather time consuming to develop and test the Ant XML required to generate and publish these metrics; combine that with configuring each CI server job to capture these metrics and you have added a fair amount of overhead.  I knew there was support for Maven-based projects within Hudson/Jenkins, but never took the time to understand why it would be beneficial. The main benefit is right there in the description, had I bothered to read it! Configuring a Maven-based job is little more than clicking a few check boxes. No need configure them in Jenkins, using the information provided by Maven, it is basically automatic. This is one interesting aspect of the Hudson-Jenkins fork. Sonatype, the creator of the Nexus Maven Repository manager and the Eclipse Maven plug-in, have chosen the Hudson side of the battle. I wonder what this means for Maven support on the Jenkins side. Obviously, it will not go away, but that might end up being a Hudson advantage in the long run. I still believe that the Jenkins community will quickly out pace the Hudson community. I knew there was support for Maven-based projects within Hudson/Jenkins, but never took the time to understand why it would be beneficial. The main benefit is right there in the description, had I bothered to read it! Configuring a Maven-based job is little more than clicking a few check boxes. No need configure them in Jenkins, using the information provided by Maven, it is basically automatic. This is one interesting aspect of the Hudson-Jenkins fork. Sonatype, the creator of the Nexus Maven Repository manager and the Eclipse Maven plug-in, have chosen the Hudson side of the battle. I wonder what this means for Maven support on the Jenkins side. Obviously, it will not go away, but that might end up being a Hudson advantage in the long run. I still believe that the Jenkins community will quickly out pace the Hudson community. |

| Deployment | I’m not going into much detail on this point, other than to say that I would like to see the deployment process completely separated from the build process, maybe even done by two different people or organizations. I have seen too many projects combine building and deploying into one system, creating artificial dependencies, time consuming, unreliable, and unmaintainable deployment processes. I have also experienced complete deployment overkill, causing simple deployments to take over thirty (30) minutes, with no real guarantee that it would be successful. Hopefully teams (developer and operations) will strive for a minimal deployment overhead/process, one that provides just enough security and control to enable continuous, rapid deployments. |

I have barely touched upon the real power of Maven and know that some people are going to say my requirements are too simple to be valid. I’m sure there are projects far more complicated than mine, but I do feel that this project is highly representative of the 80-20 rule. If developer’s can have a little self control, conform, and do what is required verses what would be really cool, simple Maven POMs should satisfy a large number of corporate projects with very little overhead. That is the goal, correct? I can even see using Maven for my toy projects; why do I want to waste time writing and maintaining a bunch of useless build scripts? I never realized that you could ease into Maven; I think that is the real point of the post! And, it is not actually a huge investment.

When I was Googling for this topic, I found many interesting articles. I truly believe the biggest reason preventing teams from evolving and adopting new approaches is simply fear, fear of change and the unknown. I still think Maven is a rather large “pill to swallow”, but have now experienced enough value to continue investing time into this technology. I took the typical developer approach and dove into Maven with little preparation or understanding… I would not suggest this approach, unless you to have lots of time to waste! If you are unfamiliar with Maven, I hope the following collection of articles will provide a quick overview of the basic concepts. I realize that some of them are a little old, but you should start with the Maven basics, and those really have not changed.

An Introduction to Maven2

Should you move to Maven2

Maven vs Ant: Stop the Battle

How to Migrate from Ant to Maven: Project Structure

Top Ten Reasons to Move to Maven 3

Maven over Ant + Ivy

Automated Deployment with Maven – Going the whole nine yards

March 1st, 2011 8:29 am

[…] improvements. I have been an Ant-man for many years, and was proficient in the “Art of… [full post] Phil Soapbox Rants and Raves continuous integrationeclipsesoftware development […]

November 29th, 2011 7:00 am

I think that the most valuable contribution from Maven are good build standards. After using Maven for over a year, I can tell that the standards save a lot of time.

However, I also noticed that Maven has still many small issues that don’t seem to be solved soon. Maven builds broke suddenly every 2-3 months in a way nobody could understand, without anyone doing changes on the build files. I believe that these issues are consequence of the lack of (what you called) ‘ThinkFirst’ by Maven Developers.

After all, our team was spending more time overcoming that many small Maven issues than fixing Ant scripts. It was much easier to write modular, reusable, standard Ant scripts that mimic Maven than guarantee Maven running for one year. I don’t think that Ant is good, but I prefer something that I understand and that behaves predictable.

I still expect that Maven will be dead soon. That another project will arise, very similar to Maven, but without its issues (better ThoughtFirst 🙂 )